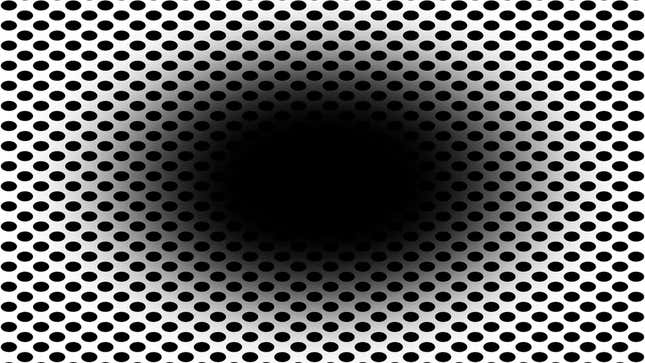

Expand the image above to fill your screen and stare at the black blob in the center. (You can also find the original version here.) Most people perceive the blob as expanding or feel that they’re falling toward the hole. This new-to-science illusion has given researchers some more insight into how human vision works, and it shows how our perception of the world is shaped by predictions our brain makes.

Unlike other black hole illusions that have resulted in someone literally falling into a big hole, this black blob—created by Akiyoshi Kitaoka as part of research published earlier this week—is set against a pattern of smaller black dots on a white background and is a completely static image. It creates a false sense of movement that also causes the observer’s pupils to expand, according to the study. The physical reaction happens no matter where the observer is, even if they’re looking at the illusion in a well-lit room where pupil adjustments aren’t needed. There’s seemingly no reason for the physical response to occur, but the researchers believe this illusion demonstrates how our brains compensate for the processing time needed to visually perceive the world around us in real-time, and that certain involuntarily reflexes aren’t necessarily controlled by someone’s physical reality.

It’s a type of optical illusion that has come to be known as “perceiving-the-present,” which was first named back in 2008. As fast as we think our brains are at processing what we perceive, it can actually take around 100 milliseconds to make sense of the data generated when light hits our retinas. Someone walking slowly can cover as much as 10 centimeters during that time, which is not insignificant, and demonstrates why our brains have needed to develop these compensation mechanisms and frequently make predictions as to what we’re perceiving and what we will be perceiving momentarily.

Another image that demonstrates this phenomenon is Akiyoshi Kitaoka’s “Asahi” illusion of brightness. Our brains perceive the white at the middle of the illusion as being much brighter than the white surrounding it, when in reality they both have the exact same RGB values, and the brightness of the image is completely uniform. Researchers have also found that a subject’s pupils will contract when observing this illusion, even when the lighting in the environment they’re physically in doesn’t change.

It’s believed that this illusion causes a physical pupil reaction because the brain is attempting to protect the retina from the sudden glare of a bright light, which can not only temporarily inhibit our ability to see but also potentially damage the retina. The center of the Asahi illusion is no brighter than its other white areas, but the arrangement of shapes and the dark-to-light gradients create a perceptual correlation to walking through a forest dense with trees and occasionally catching glimpses of the bright sun through the leaves. Even though the observer isn’t actually at risk of looking at the sun, this is what the brain is predicting will happen, and the pupils react accordingly.

In the case of the back hole illusion, researchers found that observers’ pupils expanded when looking at the image, as their brains likely perceived them to be physically moving toward a space that was considerably darker than their current environment. The brain was preemptively compensating by making the eyes ready to gather more light. The illusion of forward movement is thanks in part to the black blob’s softened edges, which create the appearance of motion blur; that’s why observers see the black blob as growing, the same thing one would see when walking towards a dark cave, for example.

It’s slightly disconcerting that, at any given time, what we think we’re really seeing could be just an educated guess that our brain is making about what we might be seeing 100 milliseconds from now—and that those educated guesses can trigger involuntarily physical responses. What’s also intriguing is that roughly 86% of the people the team studied had the physical pupil response, and they’re not exactly sure why 14% did not. What makes those people different, and does that put them at a disadvantage when it comes to navigating the world?