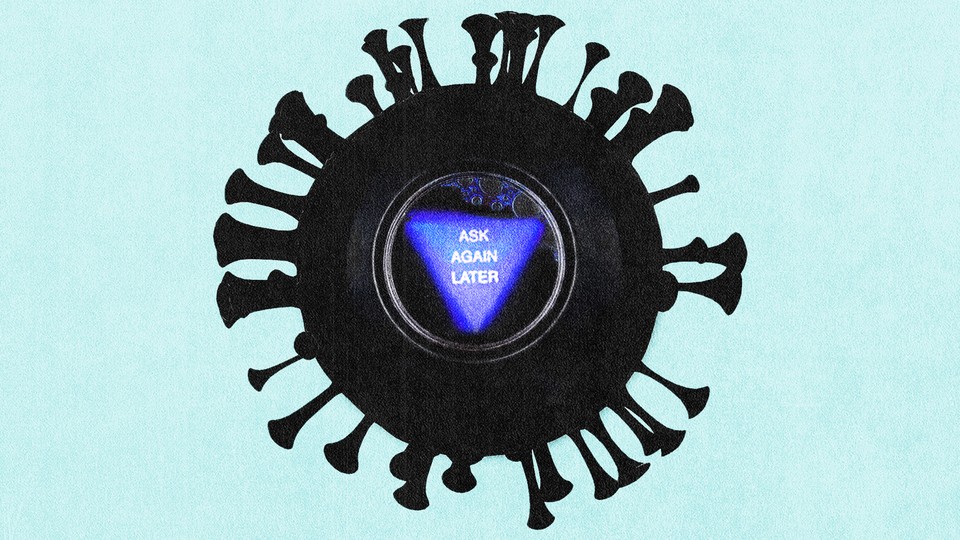

Why So Many COVID Predictions Were Wrong

The eviction tsunami never happened. Neither did the “she-cession.” Here are four theories for the failed economic forecasting of the pandemic era.

Updated at 12:13 p.m. ET on April 7, 2022.

As many prominent policy makers reckon uncomfortably with persistent inflation after months of forecasting that the phenomenon would be transitory, I’ve started making a list of other pandemic predictions about the economy that never materialized. There was the eviction tsunami and the “she-cession” and the housing-market crash, and you can’t forget the state- and local-government deficit explosion. In each case, expectations set by economists, policy makers, advocates, and businesses have not been borne out. Let’s take them together, one by one.

In August 2020, the Aspen Institute released a report warning that 30 million to 40 million people in the United States were at risk of eviction, a number equivalent to roughly one in 10 Americans. But in December 2021, Princeton’s Eviction Lab found that in the 31 cities where it had collected data, all but one recorded fewer eviction filings than the historical average. Not only was the prediction startlingly off base—evictions actually declined.

From May to August 2020 McKinsey & Company surveyed more than 40,000 people and found that roughly 25 percent of women were considering leaving the workforce “or downshifting their career” that year. As the Harvard economist Claudia Goldin has noted, much of the media coverage of this finding failed to note that 20 percent of men were also considering leaving the workforce or cutting back. A New York Times story hypothesized that the pandemic would reduce women’s share of the workforce for years to come. However, as Goldin writes in a recently released study, the labor-force participation rate for women ages 25 to 54 was the same in November 2018 as it was in November 2021: “Employed mothers, by and large, did not leave the labor force … and those who remained employed did not downshift as much as had been thought.”

Basically no one predicted the gangbusters housing market. Some economists thought home-price growth would flatten, and others thought the recession could tank the market. Businesses were pessimistic too: Opendoor, a company that buys and sells homes online, sold off roughly $1 billion worth of inventory in 2020 and paused its purchasing for several months, leading to significant losses. We now know that home prices have risen dramatically throughout the pandemic.

In the summer of 2020, fears of a state and local budget crisis were widespread. Moody’s Analytics, for instance, predicted “inescapable shortfalls” totalling $500 billion. One October 2020 Wall Street Journal headline proclaimed that states were facing their “Biggest Cash Crisis Since the Great Depression.” In July 2021, the Government Accountability Office released a report indicating that state revenues had rebounded in the second half of 2020. And although some variation exists in how well states are doing, they’re certainly not facing the crisis once predicted—many states are now even reporting massive surpluses.

If, after reading this, your reaction is to say, “Well, duh, predictions are difficult. I’d like to see you try it”—I agree. Predictions are difficult. Even experts are really bad at making them, and doing so in a fast-moving crisis is bound to lead to some monumental errors. But we can learn from past failures. And even if only some of these miscalculations were avoidable, all of them are instructive.

Here are four reasons I see for the failed economic forecasting of the pandemic era. Not all of these causes speak to every failure, but they do overlap.

Cause No. 1: Fighting the last war

In the Great Recession that started in 2008, the housing market crashed, state- and local-government budgets were decimated, and the federal government’s rescue efforts were in many ways too little too late. Early on in the pandemic, think tanks, journalists, columnists, and economists all leaned heavily on the preceding recession to try to understand just how bad things were going to get. “There was an awful lot of last-war-type thinking,” Jason Furman, the Harvard economist and former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, told me. Although looking to the past is normally a good rule of thumb for forecasters, this overreliance missed how different the Great Recession and the pandemic-induced recession were from each other.

Unlike the extended recession that began in 2008, the pandemic recession was extremely brief: It lasted just two months, from March to April 2020, making it the shortest in U.S. history.

The recession was so short in part because the United States spent more than $5 trillion in economic stimulus following the COVID-19 outbreak in an overwhelmingly bipartisan undertaking—the first pandemic bill, the CARES Act, passed the Senate 96–0, marking a shift in both parties’ willingness to enact large stimulus packages. According to the Tax Foundation, the United States had the second-largest fiscal response as a percentage of GDP of all industrialized countries, an effort that included direct checks to almost every American and generous extended unemployment benefits.

The Brookings Institution economist Louise Sheiner explained to me that Great Recession heuristics were a poor fit for this recession because the government made many people financially whole. Unemployment benefits, for instance, replaced more than 100 percent of wages for many people who found themselves without work. This ensured that people kept buying things and paying their rent. In fact, poverty declined significantly, and as researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis noted, personal savings skyrocketed. Even among folks who did lose their job, unemployment benefits led to tax revenue, both in the form of income taxes and sales taxes from benefit-enabled purchases, which buoyed state coffers.

Job recovery was also much swifter after this recession than the last. Permanent job losses took nearly eight years to recover after 2007; this time they’ve taken just two. And this success may be related to another failed prediction: that a wave of small-business failures would hinder rehiring. But, according to research from the Federal Reserve, actual closures are “likely to have been lower than widespread expectations from early in the pandemic.” Because many businesses did not permanently close, workers were able to get rehired as the economy stabilized.

These facts lead to one potential umbrella explanation for why dire warnings based on the previous recession never came to pass: Quite simply, policy makers heeded those warnings and effectively intervened.

“The eviction tsunami didn’t happen not because we wrongly warned everyone but because advocacy works and governments responded to the threat,” Diane Yentel, the president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) and a co-author of the Aspen Institute report, explained to me.

This seems partly true but also overstated. “Predictions of 30 to 40 million people suddenly being evicted—there’s a problem of face validity there,” Peter Hepburn, a sociologist and Eviction Lab researcher, told me. A recent report he co-wrote estimated that 1.36 million eviction cases were prevented in 2021 because of policy interventions such as the eviction moratoriums, emergency rental assistance, and other fiscal support. That’s a lot, but still a far cry from what many researchers had been projecting.

Not just government intervention but technology helped buffer the economic impacts of the pandemic, including food-delivery services (which kept many restaurants afloat), virtual home tours that helped enable people to continue buying and selling houses, and remote work. On that last point, Adam Ozimek, the Economic Innovation Group’s chief economist, told me he thinks a “pro-urbanism bias” is why people missed the effects of remote work on stabilizing businesses and employment rates. Ozimek argued that many people who view “agglomeration and urbanization” as extremely important trends that drive productivity and economic growth saw “remote work in opposition to that.” They didn’t factor in how many employers could function just fine with their knowledge workers scattered around the country, Zooming from their living room.

Not every bad prediction was based on expectations from the Great Recession. No one talked of a “she-cession” back then, for instance—in fact, job losses were concentrated among men. So what else went wrong?

Cause No. 2: Data overload

Private-market and survey data have proliferated in recent years, and they played a large role in the public’s early understanding of COVID-19’s economic effects. For example, OpenTable’s reservations data provided a useful proxy for whether people were avoiding indoor activities. And alongside all these new data sources was also real-time analysis: by academics in the form of working papers, journalists in the form of articles, and anyone else who wanted to participate in the form of tweets. This barrage of information was backed up by charts and graphs and tables that at times felt unending.

Data alone are value-neutral. But “a certain amount of the real-time research on COVID was knowledge-subtracting and introduced ideas into the world that were untrue,” Furman, the Harvard economist, told me.

One new source of government data that was a useful but imperfect tool was the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. First fielded on April 23, 2020, it was “designed to be a short-turnaround instrument that provides valuable data to aid in the pandemic recovery.” The relevant question asked respondents to determine their confidence in their ability to make the following month’s rent.

This survey undergirded many of the claims of a coming eviction tsunami, including the Aspen Institute’s 30-million-to-40-million estimate, but it was a “really poor barometer for how likely people were to be evicted,” Yuliya Panfil, the director of New America’s Future of Land and Housing program, told me. Panfil said that people are generally terrible at discerning their confidence in future events and that the survey was likely picking up generalized fears about the pandemic.

Other data sources proved unreliable as well, such as the McKinsey survey warning that one in four women might leave the workforce or “downshift.” Goldin, the Harvard economist, pointed out that respondents were exclusively “executives, senior VPs, VPs, senior managers, managers, and entry-level office and corporate employees, such as customer-service reps,” not exactly the embattled low-income women one might imagine being on the edge of falling out of the labor market.

Over and over again in the pandemic, the same pattern played out: A new study would circulate on Twitter, and then months later, more research would surface showing massive flaws in the earlier data. For example, right after the first round of stimulus checks went out, one study found that “most” of the money had been spent on food and gas. Six months later, more credible research found that only 29 percent of the money had been used for consumption, while the great majority had been used as savings or for paying down debt. Similarly, stories about food insecurity were pervasive. Although this matter is far from settled, recent research from the U.S. Department of Agriculture indicates that food insecurity actually did not increase in 2020.

Early in the pandemic, people were desperate for certainty about what the world would look like the next day—or even the same day. Eager for information, they may not have applied the appropriate skepticism to claims backed by “data” or “research.” One study or viral chart could bake in a narrative. It was a perfect environment for incubating bad predictions.

Cause No. 3: Bias

Many early pandemic predictions pointed toward a similar solution: a left-of-center policy agenda. A she-cession justified universal day care and paid family leave; an eviction tsunami justified stronger legal protections for renters; state and local distress seemed to require what Republicans called “blue-state bailouts.” But if this trend suggests bias at work, where was it coming from?

Goldin believes part of why many forecasts were incorrect is that much of the relevant research was produced by advocacy organizations. The McKinsey report on women leaving the workforce, for instance, was co-published by LeanIn.Org.

Similarly, the Aspen eviction study was co-written not only by researchers from think tanks and academic institutions, but also by three leaders of advocacy organizations. And those authors made judgment calls that perhaps depicted a bleaker landscape than was warranted. As Panfil explained, “The Aspen Institute study, in coming up with the largest number, the 40-million number, included not just people who said they had no confidence in making rent but also people who said they had moderate confidence in making rent.”

I don’t mean to suggest anything more sinister than motivated reasoning. Some advocates may have regarded the coronavirus pandemic as an opportunity to shoehorn in important social policies that they felt were long-justified, and, to a certain extent, they saw in the data what they wanted to see. As Hepburn, the sociologist, argued, the numbers generated by Aspen may have been useful “from a lobbying standpoint,” and Panfil noted that perhaps “it was helpful to the movement of activists who were pushing for relief measures to be put into place to cite some of these larger figures.”

Katherine McKay, a researcher at the Aspen Institute, told me that the report was useful for lobbying, not because of the eye-catching evictions estimate, but because it represented "a large group of people and organizations speaking with one voice." She said she believes the government response is the primary reason that evictions did not become an "overwhelming crisis."

Yentel, the NLIHC president, stands by the original Aspen research, calling it “not far off base.” She also noted that, in the text of the report, the researchers were transparent about a large range of potential outcomes.

However, both the Aspen Institute and NLIHC chose to make the 30-million-to-40-million figure the headline of their report and press releases. And that’s the figure media outlets repeated. Relatedly, bias may also have lurked in how the media presented research more generally. A 2020 study showed a significant negative slant in how the U.S. mainstream media covered the pandemic compared with English-language outlets outside the U.S.

Cause No. 4: Underestimating resilience

Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, marveled at “the resilience, creativity, and ingenuity of people and businesses and workers” when we spoke. He told me that “businesses really figured out a way to survive. That meant that as the economy returned to normal, there were businesses around to hire unemployed workers.” And although many small businesses closed, others opened; in fact, more small businesses exist now than did before the pandemic.

Essentially, when things get bad, most people figure it out. They find a way to make rent, to stay in business, to work a full-time job even as they care for children or sick relatives. Many forecasters seem to have underestimated this resilience.

Women were substantially burdened, many more so than men, but they did not leave the workforce en masse. As Goldin writes, “Employed women who were helping to educate their children, and working adult daughters who were caring for their parents, were stressed because they were in the labor force, not because they had left. The real story of women during the pandemic is that they remained in the labor force. They stayed on their jobs, as much as they could, and persevered.”

Low-income renters were substantially burdened as well; but an eviction tsunami did not occur. After the federal eviction moratorium expired, renters navigated a complex web of government bureaucracy to receive emergency rental assistance; soldiering through widely reported access issues, 3.5 million households received aid through the program. To make their rent payments, they also took out loans, or denied themselves other important expenses such as medicine, food, and clothing.

That affected populations are resourceful should not be surprising; the structural disadvantages facing women and low-income renters more acutely during the pandemic well predate March 2020. Persevering isn’t pretty, and in no way is the fact of perseverance an argument against expanded social support. Conditions at the bottom of the housing market were bad enough to justify government aid, eviction tsunami or not.

Housing advocates won an eviction moratorium and billions in rent relief, and state and local governments are just a bit too flush with cash. Arguably, the failed forecasting was useful. But these flawed predictions still come with a cost.

In a crisis, credibility is extremely important to garnering policy change. And failed predictions may contribute to an unhealthy skepticism that much of the population has developed toward expertise. Panfil, the housing researcher, worries about exactly that: “We have this entire narrative from one side of the country that’s very anti-science and anti-data … These sorts of things play right into that narrative, and that is damaging long-term.”

More important, if data are being misinterpreted, misunderstood, or manipulated, policy makers could design bad solutions or fail to focus on the most urgent problems. Many economists now question the wisdom of the half a trillion in aid to small businesses contained in the CARES Act. Even now, Congress has stalled on urgent pandemic funding for testing and therapeutics in part because that might require taking money back from state governments, most of which are in no need of support.

This article originally misstated the amount of aid to small businesses contained in the CARES Act.